The sci-fi author William Gibson once famously said, “The future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed,” and my primary conclusion from the conversation with Doug Shapiro is that a play on this sentiment would describe the media business as he sees it—that the future is (almost) here, and the creative power will be much more evenly distributed.

Shapiro points out that the two predominant forces in the current video media business are the traditional Hollywood studios (and similar major producers in different nations) and the set of individual social media content producers who have risen to prominence in the last decade and now account for more than 15 percent of the global media and entertainment market. The former are seeking massive audiences with an offer designed for viewing in large collective spaces (e.g., movie theatres) and the latter are seeking similar audience scale but one viewer at a time, on the smallest of viewing spaces: a mobile phone screen.

Importantly, the offers from the two protagonists in this epic duel are fundamentally different and reflect the differences in consumption device and environment; Hollywood-style blockbuster content focuses on the highest production quality, including narrative (the script) and acting talent, whereas the latter focusses on what Shapiro terms “engagement quality,” which is based on the authenticity of the creator voices and their direct interaction and relationship with their followers.

Remarkably, there is not much in between these two extremes. Shapiro has shown the traditional middle of the Zipf popularity curve has been hollowed out with the attendant investments moving to one or the other of these two camps—either to fund increasingly extravagant and expensive blockbuster content or to support more creators producing more channels and personality-driven series.

However, Shapiro argues that this binary equilibrium is about to be perturbed by generative AI (GenAI) technologies, resulting in a new content production continuum that is distributed not only between these current power bases but is extended to the unit level of any creative individual with a vision and the requisite motivation: a new human-expressive utopia.

To appreciate the uniqueness and the compelling arguments for this unprecedented future, it is instructive to first consider the evolving media positions of the past decades that have led us to the present reality that, in turn, augurs this future.

Shapiro points out that any discussion of shifting marketing dynamics comprises the interplay of three factors:

- Economics: what is viable as a business and financially sustainable

- Technology: what new service or solution can be created with the required economics

- Preference: what is desirable to the end user in a new service or solution

In our conversation with Rodney Brooks, he cautioned against “magical thinking” that typically involves being so seduced by a compelling new technology that we consequentially believe it will have exponential market uptake—a sentiment with which Shapiro agrees. He cautions against “technological determinism,” which is essentially a result of miscalculating No. 1, due to the addictive appeal of No. 2, leading to relative ignorance of No. 3.

So, let’s not fall into that trap; we’ll start with looking at the economics, then consider user preferences and then look at what AI and GenAI technologies might enable that allows a new market equilibrium.

Evolving Economics: The Distribution Moat Is Bridged

In the pre-internet age of video, television content was first provided over the air for free to antennae mounted on every rooftop, but the limited amount of content that could be delivered this way (due to spectral limits) led to alternative broader bandwidth delivery methods using either wires (in the form of coaxial cable) or home-mounted receivers to pick up modem or satellite transmission. .

The cost to deploy these new infrastructures was sufficiently high that they effectively also became scarce resources that allowed the owners of these assets to dictate the supply of content that would be made available to their subscribers. They also constructed an ancillary barrier to entry by leveraging this bargaining power to acquire preferred rights to content for periods of time, on favorable economic terms, which they then monetized in the form of packages or bundles of content channels offered at premium prices to subscribers.

Moreover, as is typical with all such bundling strategies, desirable content channels were combined with less desirable content in order to justify higher pricing by the combination of quantity and quality of content. The net effect of this practice was that the video content business was increasingly guilty of providing too many channels consumers didn’t want, with little or no choice.

Traditional media businesses effectively had established a moat that protected them from new entrants with high barriers to entry. Large-scale content distribution required significant labor effort and capital expenditure, so few companies were willing and able to make the necessary investments. The supply of distribution was therefore limited, while the demand for (some) associated content remained high. The net effect was that the cable business was one of the most profitable of the era, due to continuously increasing price points. But this led the providers to habitually overserve consumers by supplying ever more content and channels, so that viewers watched only about 7 percent of the more than 150 channels in their cable packages.

But the internet and the associated digital and web technologies removed this moat around distribution and massively reduced the cost to create digital assets that could be infinitely reproduced without degradation and then delivered as internet services. Furthermore, the cozy relationships that existed between the content distributors and the big content producers, which effectively created an additional mini-moat, was no longer sustainable, as any content could now be accessible over the web. This gave rise to a host of new content services, like YouTube, that provided a diverse array of creator-owned content for free, albeit at much lower production quality and with little or no formal script or literary storytelling.

To understand the importance of this seemingly trivial shift, it is helpful to refer to Shapiro’s characterization of the media business as essentially about monetizing attention (the number of hours spent consuming content) and monetizing engagement (the intensity of the attention paid to the content).

Shapiro identifies a key issue: Attention is finite, given the limited number of nonactive or occupied hours in person’s day. Indeed, it has now maxed out at 13 hours a day of time spent with all forms of media in the U.S., representing about 75 percent of the average person’s waking hours. So, there is little economic value left to exploit in attention.

But there is a compounding economic issue: the video market as a whole shows no growth in inflation-adjusted real terms, due to declining consumer spending on video media entertainment (as a percentage of personal expenditures), declining spending on advertising (as a percentage of total ad spend) and declining revenue and profitability for traditional TV and streaming over the past 10 years.

This is a direct consequence of the fact that the total time spent watching linear and streaming TV and video has declined more than 70 percent since 2015, with other forms of media taking the place that was traditionally held by communal TV and video viewing. Notably, the only bright spot in terms of traditional viewership is live sports, which have remained relatively stable over time in all age groups. But this unique status has driven the licensing costs up dramatically due to the limited supply and manifest demand.

So, the net of all these factors is that the economics of monetizing attention paid to traditional video media is in perennial and seemingly irreversible decline.

Parasocial Preferences: The Unexpected Arrival of Authenticity

Clayton Christensen’s famed treatise The Innovator’s Dilemma identifies such constrained environments as ripe for disruption, either by the arrival of an option with superior economics and acceptable appeal—an existing market disruption—or an alternative solution or service that creates a new competitive market.

Traditional corporate content providers—as is the wont of all incumbents—have retained their focus on scripted content with ever-higher production quality. But this comes at ever-higher costs (Shapiro estimates ~60 percent higher expenditure over the past five years) and requires massive blockbuster popularity in order to be profitable. The risk-reward profile of original scripted content is consequently less attractive than that derived from leveraging existing, proven intellectual property (IP) in the form of sequels and branded series, like the Marvel Cinematic Universe, or franchises, such as Fast & Furious, Mission Impossible or Star Wars. But this effectively constrains the economic potential to the known perimeter. An early indicator of this creative and consumer conservatism is provided by the fact that in 2024 more than two-thirds of the top 100 movies were based on existing IP.

The recent attempts to find a new source of revenue by the studios via the launch of streaming services has largely backfired, as Shapiro has shown that streaming media returns three times less revenue per hour viewed than traditional linear TV, which remarkably still composes 66 percent of all video revenues. Due to these challenging economics, streaming services also rely heavily on licensed content, which currently represents 80 percent of the viewing time for the top 100 streamed titles.

But, set against this constrained backdrop, over the last decade or more, an alternative service has appeared in the market that exploits the other quality dimension: engagement.

This shift was fundamentally enabled by the technological innovations that created the mobile internet. Music was undoubtedly the first media form to see this behavioral change, with consumption shifting to mobile devices that replaced dedicated MP3 music players that could not support music streaming. And with the deployment of higher bandwidth wireless technologies (LTE, 5G), video content followed suit, spawning a wholesale change in consumer behavior to value access to content anytime, anywhere.

This new “expressed preference” precipitated a new market-type disruption—the mobile media market—which was defined by smaller screens, intrinsically shorter interaction times and lower service expectations. Importantly, the limited screen resolutions and sizes allowed lower fidelity content to be relatively indistinguishable from high-quality production content, and the experience and acceptance of call drops and web session interruptions primed users to tolerate some variability in the video stream. And with the rise of adaptive streaming for web video, the streams no longer froze, they just dropped down to a lower resolution when bandwidth was in short supply.

But there was one more defining factor that became a characteristic of this new market, the emergence of a new type of content: user-generated content (UGC).

The defining attribute of UGC is the personal relevance or emotional and social engagement users feel over the scripted productions from the corporate media companies. Critically, studies by YouTube reveal that 76 percent of Gen Z viewers prefer social platforms, as the content “better reflects them.” Moreover, the engagement with this type of content has a strong social and parasocial aspect, which can be fully understood by reference to the human brain and the associated theory of mind and mentalizing processes in the neocortex, with these parasocial relationships replacing the traditional human physical-social relationships.

Marshall McLuhan famously argued that “the medium is the message,” meaning that the way that content was packaged and delivered was more instructive than the content itself. And it seems that the new message is that more engaging, authentic, cybersocial and parasocial content is what consumers want, with UGC now reaching around 25 percent of all video consumption by time spent.

So now we have a media market with two components, one defined by high-production value content with large-scale narratives and mass market appeal, and the other defined by lower production content, with individually appealing narratives and para/cyber-social appeal. There is an inherent tension between these two media forces, as the costs of the former are $1 million to $2 million per minute today, compared to as little as a few dollars or cents per minute for basic UGC content (the nominal cost of recording and streaming content from a mobile device). And since media attention time is fixed and cannot grow, every minute spent consuming UGC results in increasing economic stress on blockbuster content producers.

Transformative Technology: Enter Generative AI

We have focused above on the changing economics and user preferences, but the third leg of the tripartite equilibrium is technological change; there is the potential for a new technological solution to rebalance the market dynamics. And GenAI as a general-purpose technology with undeniable potential for automated text generation, video creation and production workflow optimization, clearly could do just that.

Shapiro summarizes this potential succinctly by arguing that GenAI could make the cost to produce high-quality bits asymptotically zero, driving similar disruption in the video content production market, as the internet did for the content distribution market. But the rise of GenAI has the potential to do two critical things that can change the status quo:

- Change the economics to produce high-quality content

- Change the engagement by producing new types of content

Let’s look at these two in turn.

Change in Economics: AI has already massively increased the ability to produce video special effects (VFX) via CGI and to enhance content via de-aging, or scene disposition or transformation. However, the technology costs and the number of production processes and steps have also increased as a result. But now GenAI offers the potential to automate and augment these processes by, for example:

- Reducing the effort required to generate and experiment with different content options, scenarios, special effects or even short pilots

- Reducing the number of process steps by allowing a parametric description of the story and required content/scenes to automatically generate high-quality content

- Reducing the effort to post-process content to create different variants, with different viewpoints and narrative arcs, in different languages and scenescapes

Importantly, although the first iterations of most GenAI tools necessitated giving up creative control, as the entire output was produced from a series of initial prompts, Shapiro points out that this was simply a product of the facile initial implementations that were designed to please the ad hoc creator, much like early LLMs were designed to delight the casual producer of textual responses. But GenAI tools have evolved markedly over the past months to allow an impressive degree of creative control. In fact, as Shapiro puts it, “there is a tremendous amount of human intentionality in anything good produced by AI.”

And it is in fact highly unlikely that we will see a world in which there is fully automated video production with no human involvement because, to paraphrase David Eagleman, there is nothing more important in literature [art] than feeling the beating heart of another human reaching across to you through the page [medium]. In other words, humans seek out and are extremely sensitive to connection with another human.

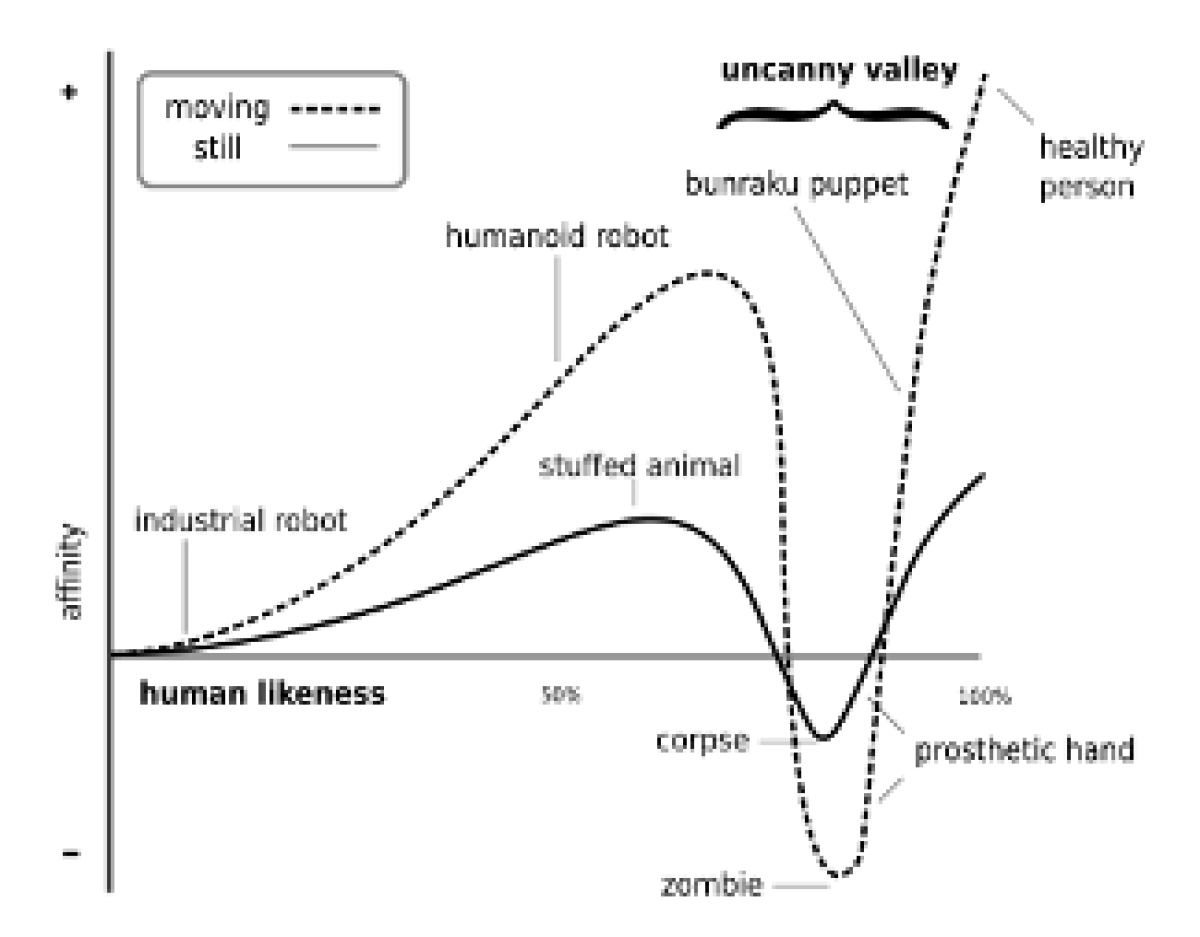

Indeed, it is this very sensitivity that gives rise to the phenomenon known as the “uncanny valley,” depicted in the figure below, in which there is a negative emotional response toward robots that seem almost human, due to the cognitive dissonance that arises from difficulty in categorization as well as an amplified form of out-group identification (and rejection), with motion only compounding this effect.

It is reasonable to assert that these uncanny valley phenomena exist due to the absence of an insufficiently complete “world model” that describes human interaction and movement accurately. The application of current GenAI tools to the video content space is effectively lacking the ability to autonomously create plausible realities, just as we have found for the applicability of current GenAI models to real-world problems throughout this series.

The net conclusion is that Nicolas Cage’s concern that “I am a big believer in not letting robots dream for us. Robots cannot reflect the human condition for us” is not likely to be justified in the foreseeable future.

Change in Engagement: For many years, AI tools have not only been used to create special effects through CGI but also to refine algorithms that match content with consumer preferences and to synthesize or adapt speech (and create subtitle text from speech) to increase the impact or accessibility of content. But now GenAI offers the potential to also manifestly enhance the consumer sense of engagement or personal immersion by automating the augmentation of content to match personal preferences. For example:

- Increasing the ability to dynamically personalize content and narratives based on user preference or persona

- Increasing the ability to create multidimensional physical worlds or views, offering unparalleled experiences with previously impossible shots

- Enabling co-creation in storytelling, allowing a greater exploration of narrative space

- Enabling the expansion of existing content or creator universes with production of high-quality fan-generated content with associated communities

- Enabling anyone with an idea to become a creator of content, without requiring significant capital investment or expertise

Reflecting on all the above, a probable outcome is the rise of a new content market that is characterized by professional-quality UGC with a unique combination of:

New video media market = optimized engagement + professional production + affordable economics

Importantly, this new reality applies equally across all types of content due to the widespread availability of state-of-the-art GenAI tools at attractive price points. So, one can imagine the following summary of our impending future:

- Hollywood blockbusters can reduce the cost of special effects and large parts of the entire production process.

- UGC gets closer to production quality and continues to expand its parasocial and cyber social engagement.

- New types of content emerge, with first-person insertion, multiple views, different endings and narrative options, which continues to explore/exploit the engagement and personalization angles.

- Hollywood creators use the same tools to escape from the constraints of Hollywood and produce high-quality scripted content with limited resources and without requiring traditional Hollywood financing and the associated compromises.

Consequently, it is reasonable to conjecture that what will emerge is a continuum of content ranging from hyper-personalized (individual consumer) to micro-communities (10 to 100 consumers) to social communities (100s to 1000s of consumers) to mass parasocial communities (millions of consumers) to mass-market blockbuster scale (100s of millions of consumers).

But this will require overcoming current fears about the potential of GenAI. Fear of technology has always been commonplace in the creative arts. In David Hajdu’s new book, The Uncanny Muse, which describes the role of technology in the evolution of musical performance and recording, he writes, “The fear of machines making art runs especially deep for cutting into one of the human species’ few claims to a special status in the universe, where ever-growing scientific knowledge makes us feel ever smaller.” And the movie and TV industry has been no exception to this over the years, with Charlie Chaplin famously arguing, “Talkies are spoiling the oldest art in the world—the art of pantomime. They are ruining the great beauty of silence.”

Hajdu further reminds us of the quote by David Sarnoff, the original head of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), in 1956: “The liberal arts should not shrug off advances in science and technology as too technical to understand, and engineers at their end should not regard music and the arts as outside their natural domain. For more than a quarter of a century, the entertainment arts have felt the magic touch of electronics. As a result, music, drama, motion pictures, the phonograph, and even journalism have taken on new dimensions.”

This view has turned out to be incredibly prescient, with a multitude of technological shifts in the content industry—from Chaplin’s objection to microphones to the introduction of home video recorders and DVDs to the introduction of video special effects tools and CGI—all giving rise to similar levels of consternation as expressed about GenAI today.

The Future Starts Where?

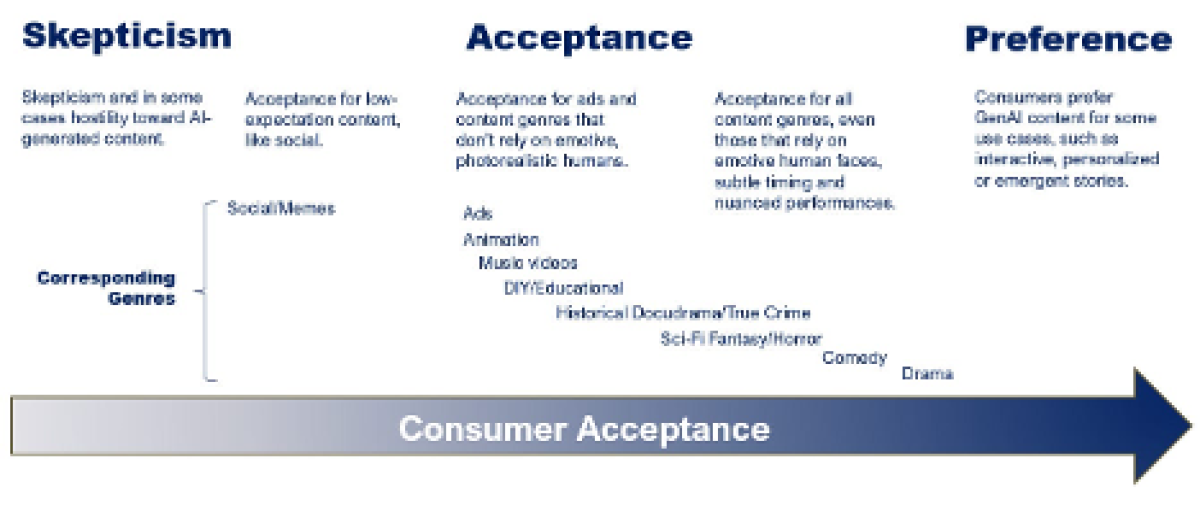

Given the above, it is entirely reasonable to conjecture that the same cycle of rejection and then adoption will follow once again. But how and where will the revolution begin? Shapiro has outlined a likely phasing, as shown in the figure below. He foresees that change will start in the social content domain, with content like that created by MrBeast, which does not require the same type of narrative story—everything just “happens”—and for which visual continuity scene –to scene is also less important. When these simplifications are coupled with the need to endlessly differentiate—and at speed—to appeal to the parasocial audience, there will be a manifest benefit from the elevated production and process automation possible using GenAI.

Next in the sequence will be the generation of content for ads, due their simple narratives, short form and intentionally imaginative propositions. A recent AI-generated ad for Volvo that was produced by a single creative designer in 24 hours is the poster child for this potential for advertising content.

Similarly, cartoon-type content focused on younger audiences will see rapid adoption, as there is also less of an uncanny valley effect or the need for rigorous continuity. Digital video giants like CoComelon—the most popular children’s program in the world, which was started by a couple for the benefit of their own children and then morphed into a global phenomenon—is perhaps the epitome of the new potential in this content realm.

Shapiro then sees short-form instruction, DIY and educational videos utilizing GenAI allowing the recorded video content to be augmented with post-processing and explanatory animation added. The same applies to docudramas and true crime, for which there are also lower fidelity and continuity requirements for simulated depictions and reconstructions of past events.

Next up will be science fiction, fantasy and horror, which require high production values and continuity, but, given that the primary characters are frequently not human, uncanniness might actually be a virtue in these genres, so these content types are also candidates for GenAI technologies to be deployed with limited negative consequences.

Finally, based on the successes and failures experienced in these content realms, GenAI-assisted content will likely become part of mainstream, scripted and human-centric content.

What does this do to the market as a whole? Clearly, according to the above phasing, the innovation will be led by the long tail of UGC, for which the high degree of process automation and superior content generation capabilities will have an outsized impact. So, one can expect the long tail to become even longer. On the other end of the scale, Shapiro believes that the incumbent Hollywood mainstream will be slower to adopt these technologies and so will effectively be constrained to operate in the high-production content domains in which they increasingly operate today.

However, due to the tension in the “big corporate” versus “creative” relationship, some early adopter Hollywood-creator types will likely be enthusiastic adopters of GenAI, in order to break the codependency with the studios and their financing and resources, and to strike out on their own for the first time. One example of this phenomenon is the recent creation of an AI innovation lab in AGBO, the media production company created by the Russo brothers.

Putting this all together, it seems likely to me that GenAI will lead to a democratization of creativity, making powerful creation and production tools increasingly available to everyone. This will necessarily lead to a remapping of the popularity curve, to create a longer tail on one end, a challenged but persistent blockbuster segment on the other end and a new burgeoning midsection of the market. Importantly, this segment will inherit the experimental and exploratory nature of the UGC segment and the scripted narrative storytelling from the Hollywood segment, to produce content that is both original and highly compelling and with economics that support a wide focus across different communities and market segments.

Are We There Yet?

While the preceding discussion sounds like a utopian ideal, much remains to be resolved for this to become a reality. In particular:

- AI models need to embed world models: To date, these models have been trained on video and textual descriptions of that video and have learned to interpolate and extrapolate from this trained set. But this is, at best, an incomplete inferred reality of the world that will never be sufficient to correctly and completely capture the richness of the world humans experience. A persistent theme in this series is that AI models will require a multitude of experiential world models that abstract the world across all dimensions to be developed and incorporated.

- Super-exponential reduction in cost: The cost to produce video for a blockbuster-quality film will have to fall by a factor of 100,000 (from $1 million or more per minute today to a few tens of dollars per minute) to fully democratize these tools. Such cost reductions are extremely challenging even in the silicon world that has benefited from Moore’s Law efficiencies. And, currently, there is a tension between the increasing costs associated with the state-of-the-art models versus markedly decreasing costs for training and inference-optimized models (cf: OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4.o versus DeepSeek R1).

- Infinite content meets finite demand: The 66 percent of video revenue that comes through pay TV channels will now be subject to redistribution to new types of content, but Shapiro has shown that linear TV monetizes at rates 50 percent higher than streaming services like Netflix and threefold higher than YouTube per hour. So, redistribution of these monies may lead to an insufficiency of capital in the market as a whole, resulting in attenuation of this market evolution.

- Platforms police the future: The smallest of the web platform companies is bigger than all the content companies combined in market capitalization and revenue. The platform companies already play a significant role in connecting UGC with consumers, and as GenAI technology leaders, they will likely be the gatekeepers and toll-takers of the future of this media, just as they are for the digital markets for music, books, journalism, etc.

- Whose copyright is it anyway? Any discussion of GenAI in the context of the arts and media production would not be complete without recognizing the thorny issues and compelling arguments around IP copyright protection versus “fair usage” for transformative purposes. There is nothing that can add to this debate, other than to say that the ownership of GenAI-assisted created content will also need much greater clarity to allow the value to be fairly assigned in this new democratized content creation regime.

In summary, I think we have learned a great deal from the conversation with Shapiro, much of which supports the eight key findings from our AI Impact interview series to date, from a technological and humanistic standpoint. But the dynamics of the media and entertainment industry in terms of economics and consumer preference shifts are quite unique and will effectively dictate the impact of GenAI on this most personal and human-resonant of creative spaces.