From the collapse of the Berlin Wall to the most recent proclamations from Washington’s foreign policy think tanks, a persistent illusion has shaped American strategic thinking: the belief that great-power rivalry, in particular the current competition between the U.S. and China, will follow the logic of the Cold War.

The assumption is seductive—that adversaries can be contained, alliances can be frozen into blocs, and victory will come through ideological exhaustion. But China is not the Soviet Union. It is not an isolated command economy, nor an empire straining under the weight of its military overreach. It is a globalized, tech-powered, civilizational state with capital, competence, and continuity—one that refuses to play the part scripted in Moscow.

No historical rivalry has left a deeper imprint on U.S. strategic doctrine than the Cold War. For nearly half a century, the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a systemic struggle—military, ideological, and economic. Yet the Soviet model was brittle. Behind its façade of superpower status lay a stagnating economy. Its political order—rigid and authoritarian—routinely suppresses dissent across its imperial borders. Technologically, the USSR lagged far behind in innovation; its computer industry, for instance, produced only thousands of machines compared to the millions manufactured in the West. Its alliances were coerced, its innovations lagged behind, and its industrial system collapsed under its own contradictions. When the USSR finally disintegrated in 1991, America emerged triumphant—armed not only with military superiority, but with a playbook.

That Cold War playbook—containment, deterrence, ideological messaging, and eventual collapse—became America’s conceptual toolkit for managing future rivals. American policymakers are now trying to apply the same formula to China. But this time, the target is not a fragile ideological bloc sustained by fear and subsidies. It is a sovereign, capitalist-technocratic hybrid with strategic discipline and technological ambition. Unlike the Soviet Union, which was largely excluded from the Western economic system, China has become central to it.

China’s rise is not a miracle—it is a return. For much of recorded history, China was the world’s largest economy. In 1820, it accounted for over 30 percent of global GDP. The subsequent century of humiliation at the hands of European powers is still seared into its national psyche. China never allowed its economy to be fully integrated under American terms. Its “reform and opening” process, begun in 1978 under Deng Xiaoping, was always accompanied by state-led strategic control. While Beijing joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, it never surrendered its economic levers to the market or to foreign capital.

The American attempt to “contain” China as if it were the Soviet Union is not only misguided—it is dangerous. Proponents of a Cold War strategy advocate for a global, systemic form of containment, designed to trap the adversary under the weight of its internal contradictions. This logic envisioned an expansive, resource-intensive campaign to confront Soviet power across every region and domain.

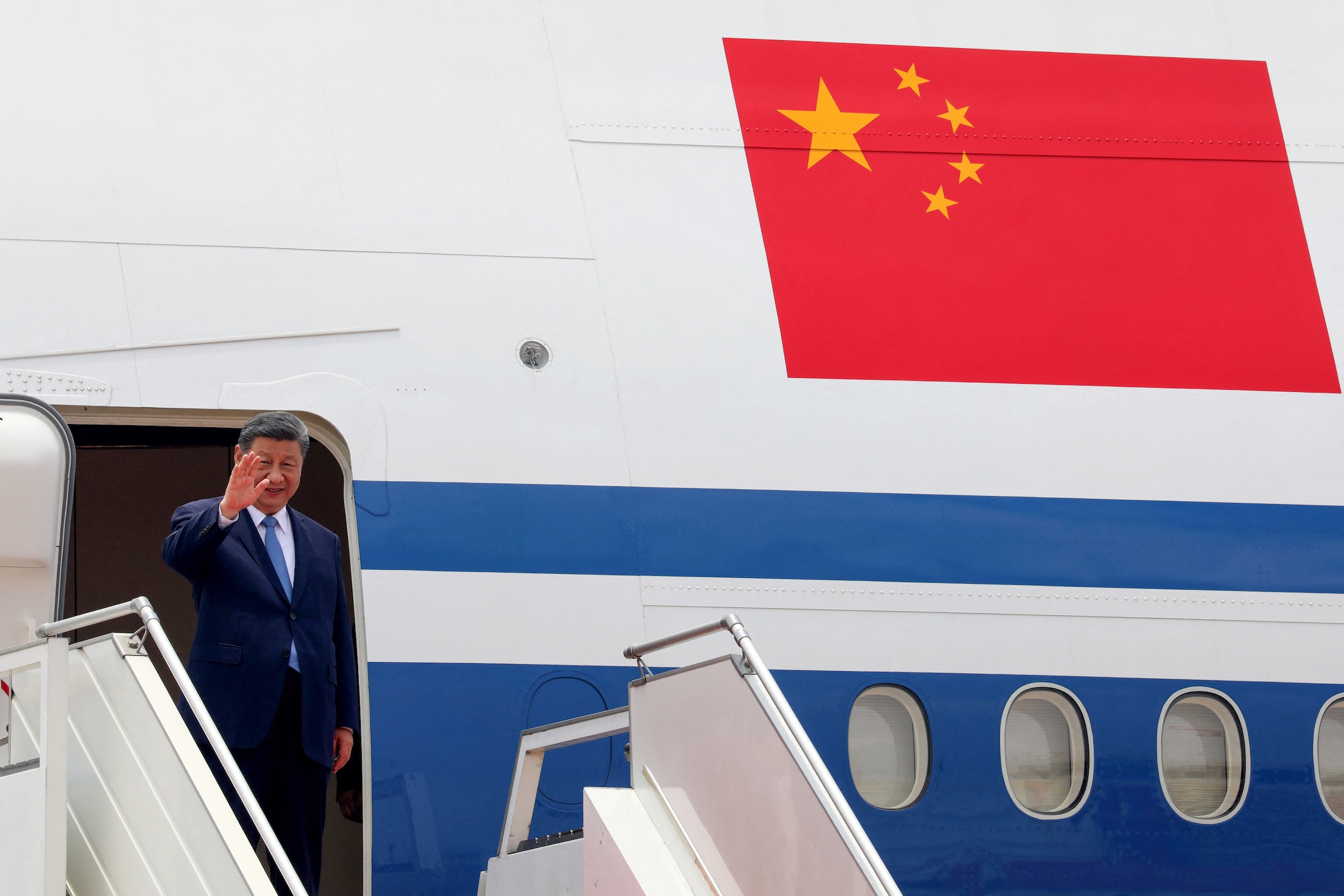

STR/POOL/AFP/Getty Images

But applying this playbook to China runs afoul of present-day realities. The United States is no longer the industrial behemoth it was in 1950; we have a post-industrial economy, heavily reliant on dollar supremacy and global financial leverage. China, by contrast, is the factory of the world—deeply embedded in global supply chains, commodity flows, and infrastructure networks. Put simply, America can no longer afford a strategy of systemic containment that treats the entire world as a single theater of confrontation.

From Latin America to Africa, Southeast Asia to the Gulf, China is not merely participating in globalization—it is shaping the very terms of the global digital transition. Through cost-effective technologies, China is setting the conditions under which much of the world is entering the digital age. From Huawei‘s 5G networks and cloud infrastructure to DeepSeek’s frontier AI models, and from BYD’s electric vehicles to Chinese-built robotics, Beijing has driven technological diffusion at an unprecedented scale. China is no longer just competing within the existing system—it is defining a new geopolitical domain altogether: geotechnology.

In addition, conversations about building universal coalitions to counter China often miss the structural contradictions within America’s own alliance network—particularly in East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Arabian Gulf, and even among transatlantic partners. While many allies share concerns about China’s assertiveness, they do not share Washington’s appetite for global confrontation, especially when their economic futures are intertwined with Chinese trade, capital, and infrastructure. The notion of offering market access in exchange for geopolitical alignment—a hallmark of U.S. statecraft during the Cold War—is increasingly obsolete in today’s political climate, with its populist emphasis on the American working class. Given the prevailing discourse in American domestic politics, strategic generosity is no longer politically viable.

Rather than pursuing a nostalgic vision of Cold War containment, the United States must leverage this moment of global flux to rebuild its industrial base, strengthen its domestic innovation ecosystem, and capitalize on the geopolitical contradictions within the Indo-Pacific region. These include tensions between China and India, maritime disputes with ASEAN nations, and regional anxieties about overdependence on Beijing. The goal should not be to force alignment but to shape incentives for other regional powers to view Chinese hegemony as a threat to their national security.

Most importantly, this competition is not ideological. It is technological, industrial, and geopolitical—and it should not be allowed to spiral into a world war. The task before the United States is not to wage a moral crusade against an “evil empire,” for this competition will not be won through surrender or collapse, but by sustaining strategic advantage—through reindustrialization, socioeconomic resilience, and order-building.

China is not the new Soviet Union. And this is not 1955. It is 2025. And the future will not follow the path of the past.

Mohammed Soliman is a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute, a member of McLarty Associates, and a non-resident senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. On X: @ThisIsSoliman.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.