“Oopsie, too late.”

That was the response from El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele last weekend after reports emerged that a U.S. federal judge had attempted — and failed — to block a pair of deportation flights carrying Venezuelan migrants accused of gang ties to his country.

By that time, the flights had already landed in San Salvador. Among those on board was Francisco Javier García Cacique, a 24-year-old barber from Venezuela who had entered the U.S. in September 2023, seeking asylum after spending several years living and working in Peru and Colombia. He was detained shortly thereafter.

After days without hearing from her son, his mother, Mirelys Casique, began receiving dozens of WhatsApp messages asking if one of the detainees seen in a video posted by Bukele was Francisco.

Today, the first 238 members of the Venezuelan criminal organization, Tren de Aragua, arrived in our country. They were immediately transferred to CECOT, the Terrorism Confinement Center, for a period of one year (renewable).

The United States will pay a very low fee for them,… pic.twitter.com/tfsi8cgpD6

— Nayib Bukele (@nayibbukele) March 16, 2025

“It’s him. It’s him!” she cried upon seeing the footage of shackled men with shaved heads being forced off planes and into El Salvador’s notorious Terrorism Confinement Center, known as Cecot. She froze.

Her son was thousands of miles from home, locked inside a prison complex infamous for extreme overcrowding, abuse and reports of torture. “We recognized him by his tattoos, by the ones on his right arm,” Casique told Newsweek in an exclusive interview.

“My children recognized him too. They searched through photos, looked everywhere until they found him.”

‘He Is Not a Criminal’

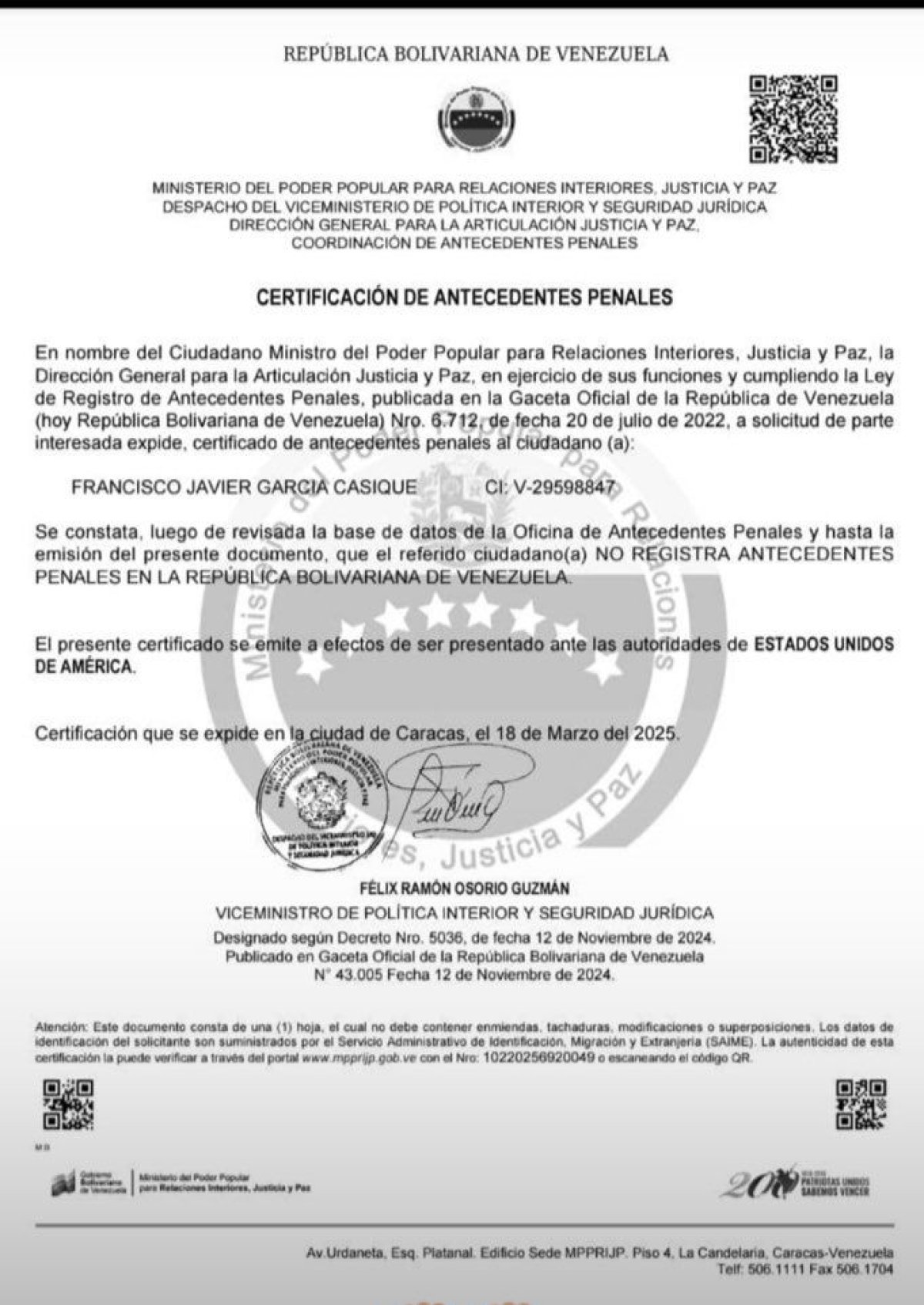

Casique refuses to accept the U.S. government’s justification for sending her son to El Salvador. The Trump administration has defended the move, claiming the deportees are all members of the notoriously violent Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua (TdA), which is now designated a foreign terrorist organization. But some of the deported men, including Francisco, do not appear to have any criminal record in either the U.S. or Venezuela.

“My son is not a criminal; he is a barber,” Casique said. “Since leaving Venezuela, he has worked as a barber, starting little by little. He entered the United States when there was a humanitarian channel to help people from our country.”

After he was detained at the border in 2023, Francisco spent two months in a Dallas detention center before a judge ruled he wasn’t a threat and released him with an electronic tracking device, his mother said. He frequently called home, sharing his dream of saving enough money to buy land and open his own barbershop—just like the one he had worked at for the past year in Longview, Texas.

“He would say, ‘I see myself doing it on my own. It doesn’t matter, I’ll push through. I’ll build my little house, start my business, and go from there.'”

Courtesy of Mirelys Casique

Less than a week ago, Francisco told relatives he expected to be deported to Venezuela after being arrested by immigration officials on March 2. His family remains uncertain about the circumstances of that arrest. “Authorities arrived at Francisco’s door and took him into custody,” his mother said.

Francisco’s sudden deportation abruptly ended his six-year pursuit of a better life—a struggle shared by many young Venezuelans born under the socialist regime of Hugo Chávez. The flight had been scheduled for last Friday, and his family in Maracay had planned a gathering to welcome him home. It never happened.

Families in Panic

On Saturday, President Donald Trump announced that he had invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, which allows the U.S. to deport noncitizens without legal recourse, including the right to appear before an immigration or federal court judge.

The deportation of 238 Venezuelans to El Salvador this weekend was the first instance of the 227-year-old law being enforced under the new administration. It has left families in panic, fearing that their loved ones were handed over to Salvadoran authorities by the Trump administration without due process.

“They shaved his head, beat him, and forced him to bow,” Casique told Newsweek, her voice trembling. “They treated him like a criminal, like a dog. Why? What proof do they have? Where’s the evidence linking him to any crime?”

El Salvador Presidency

Reports suggest that some of the Venezuelan detainees were targeted simply for having tattoos, even when there was no proven connection to TdA. For some, a simple marking on their skin became grounds for suspicion. One Venezuelan man was detained, his attorneys claim, in part because of a Real Madrid tattoo on his arm.

“They might see a rose tattoo, a crown, or even the word ‘family’ and decide that’s enough to label someone a criminal,” Casique said.

Newsweek reached out to the State Department and ICE with specific questions about Francisco Javier García Cacique’s case on Wednesday but has yet to receive a response. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has said that federal privacy restrictions prevent U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) from discussing specific cases.

Casique said that as of Thursday, she had not heard back from Francisco after his electronic monitor vanished from ICE’s online locator. She said she had been contacted by ACLU attorneys in the U.S. and had since received messages from Venezuelan Minister of Interior, Justice and Peace, Diosdado Cabello, acknowledging her son’s case.

‘The Less We Know About You, the More Dangerous You Must Be’

Immigration advocates have expressed outrage over the lack of due process in these cases, specifically after U.S. officials acknowledged in a court filing Monday that many people sent to El Salvador do not have criminal records, while insisting all are suspected gang members.

Courtesy of Mirelys Casique

“The lack of a criminal record does not indicate they pose a limited threat,” said a sworn declaration in the filing, adding that along with their suspected gang membership, “the lack of specific information about each individual actually highlights the risk they pose.”

“It’s looking like a monumental, tragic screwup,” said Adam Isacson, a migration expert from the nonprofit Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA). “The idea that the less we know about you, the more dangerous you must be—so we strip you of all rights—is as reckless as it is unhinged.”

Neither the U.S. nor Salvadoran authorities have presented evidence linking the majority of the migrants on the deportation flights to TdA. For now, Francisco is believed to be inside Cecot, with no word on his fate.