While Corporal punishment has been banned in most states in the U.S. since the mid-1990s, a number still allow it in schools, predominantly those in the Southeast.

In some states, while inflicting physical punishment on children in schools is banned, incidents of its use in schools still occur, the nonprofit organization Lawyers for Good Government reported.

Why It Matters

While some believe that corporal punishment is necessary to teach discipline and obedience to children, others feel that it is harmful to their welfare and infringes on parents’ rights.

There is also concern about disabled children and children of color being the most targeted by corporal punishment. Lawyers for Good Government reported that Black children are involved in 37.3 percent of corporal punishment incidents in public schools, while disabled children make up 16.5 percent of incidents.

What To Know

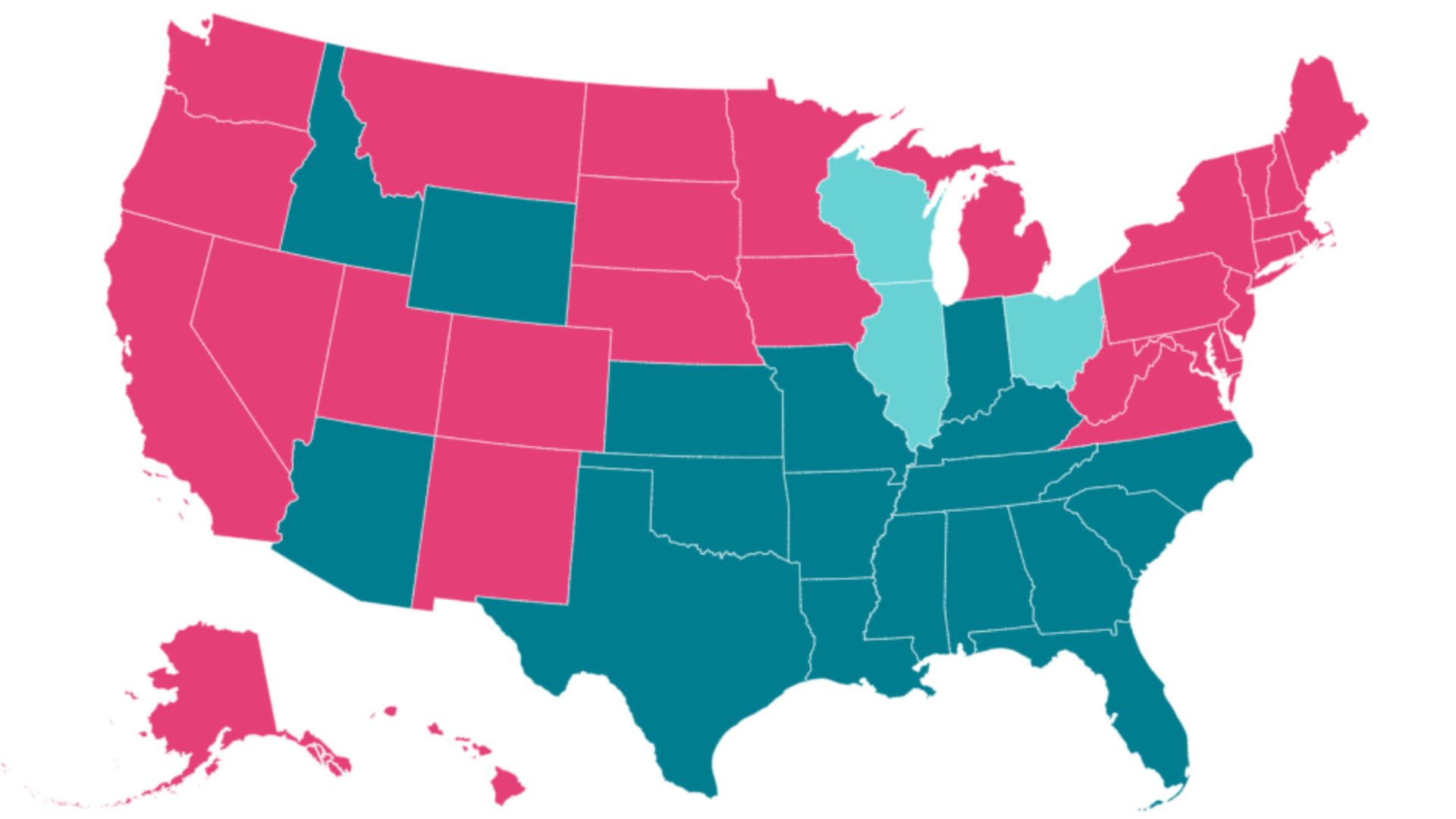

States like Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina and others in the Southeast all allow schools to use corporal punishment on children.

However, Florida recently changed its rules so that parents have to give consent.

In the West, Idaho, Arizona, and Wyoming also allow the punishment.

However, all Northeastern states have banned the punishment, alongside many states in the Midwest like Michigan, Minnesota, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Montana.

On the West Coast, California, Oregon, and Washington have also banned corporal punishment in schools.

In Illinois, Ohio and Wisconsin, while corporal punishment is banned in schools, there are still reported cases of it happening, according to Lawyers for Good Government.

Reasons for these regional differences in stance are multifaceted, but the support of corporal punishment is “largely tied to cultural norms,” Emily Douglas, a professor in the department of social work and child advocacy at Montclair State University, told Newsweek.

This can include “religious influences, what your neighbors or community does, and reliance on how one was raised,” she said, all of which influence how parents decide to raise their children.

Looking at the divide between the states that allow corporal punishment in schools and those that don’t, Douglas said, “there are cultural and normative differences between different regions of the U.S. in many different aspects of life and the reliance on and belief in using corporal punishment is one that has persisted.”

“The South tends to be more culturally, religiously, and politically conservative,” Elizabeth Gershoff, a professor in the department of human development and family sciences at the University of Texas at Austin, told Newsweek. She added that these factors can suggest whether schools use corporal punishment.

Gershoff also said that it is important to know that “the vast majority of public schools in the U.S. do not use corporal punishment, and this is true even within states where it is legal.”

Some may see it as “an effective way to change a child’s behavior for the good,” Douglas said, while others “may not like the idea of hitting a child, but they like to have it as a last possible option for when they have run out of other solutions.”

While “social science research has been consistently clear that the use of corporal punishment is not good for children,” schools also “may like to use it, because it may bring about a quick outcome, even if those outcomes are not enduring and are eventually related to other problems,” she added.

What People Are Saying

Professor Elizabeth Gershoff told Newsweek: “The decreasing rates make clear that school principals either realize that school corporal punishment is not effective at improving student behavior, that it is not necessary, is cruel and physically harmful, or that it could lead to lawsuits from parents of children injured by school corporal punishment. Decreasing rates make it easier for states to ban school corporal punishment because so few schools still use it and defend it.

She added: “The potential harms linked to corporal punishment are so well-known now and thus principals are less inclined to use it and parents are less inclined to accept it.”

Sarah Font, a professor of sociology and public policy at Washington University in St. Louis, told Newsweek: “Broadly speaking, support for corporal punishment is driven by a belief that it is necessary or at least effective in deterring disobedience and instilling proper respect for authority figures. So places where parents continue to use corporal punishment at high rates may also support its use in schools.

“Often, individuals who experienced corporal punishment themselves believe that it helped keep them in line, and research communication has not dispelled the myth that corporal punishment improves long-term behavior. Places that have outlawed it might consider it an infringement on parents’ rights or raise concerns about use of corporal punishment on students with disabilities.”

Justin Driver, a professor of law at Yale Law School, told Newsweek: “Corporal punishment in schools is a barbaric measure from a bygone era. The notion that hitting students is somehow necessary to maintain order and discipline in schools is belied by reams of research. The Supreme Court should revisit this issue soon and overturn its profoundly misguided decision in Ingraham v. Wright (1977).

“The sooner American society abolishes corporal punishment, the better. Over time, more and more states have abolished corporal punishment—only two states had abolished corporal punishment in 1977—but this injustice requires national action.”

He added: “The trend of abolition has slowed to a crawl, with a handful of southern jurisdictions accounting for the lion’s share of—let’s face it—physical assaults of students. The terminology of ‘paddling’ fails to capture the injustice that rests at the heart of corporal punishment.”

“Public school students are the only group of people in American society who government officials strike with impunity for modest transgressions.”

What Happens Next

As there has been a consistent decline in the use of corporal punishment over the past few decades, Douglas said, “there is no doubt that these trends will continue to shift.”

“Even though there are regional differences throughout the U.S., there have been declines across the board.”