The movement to drastically cut and even eliminate property taxes, which local governments heavily rely on to fund crucial public services, is gaining momentum in Republican-led states across the country.

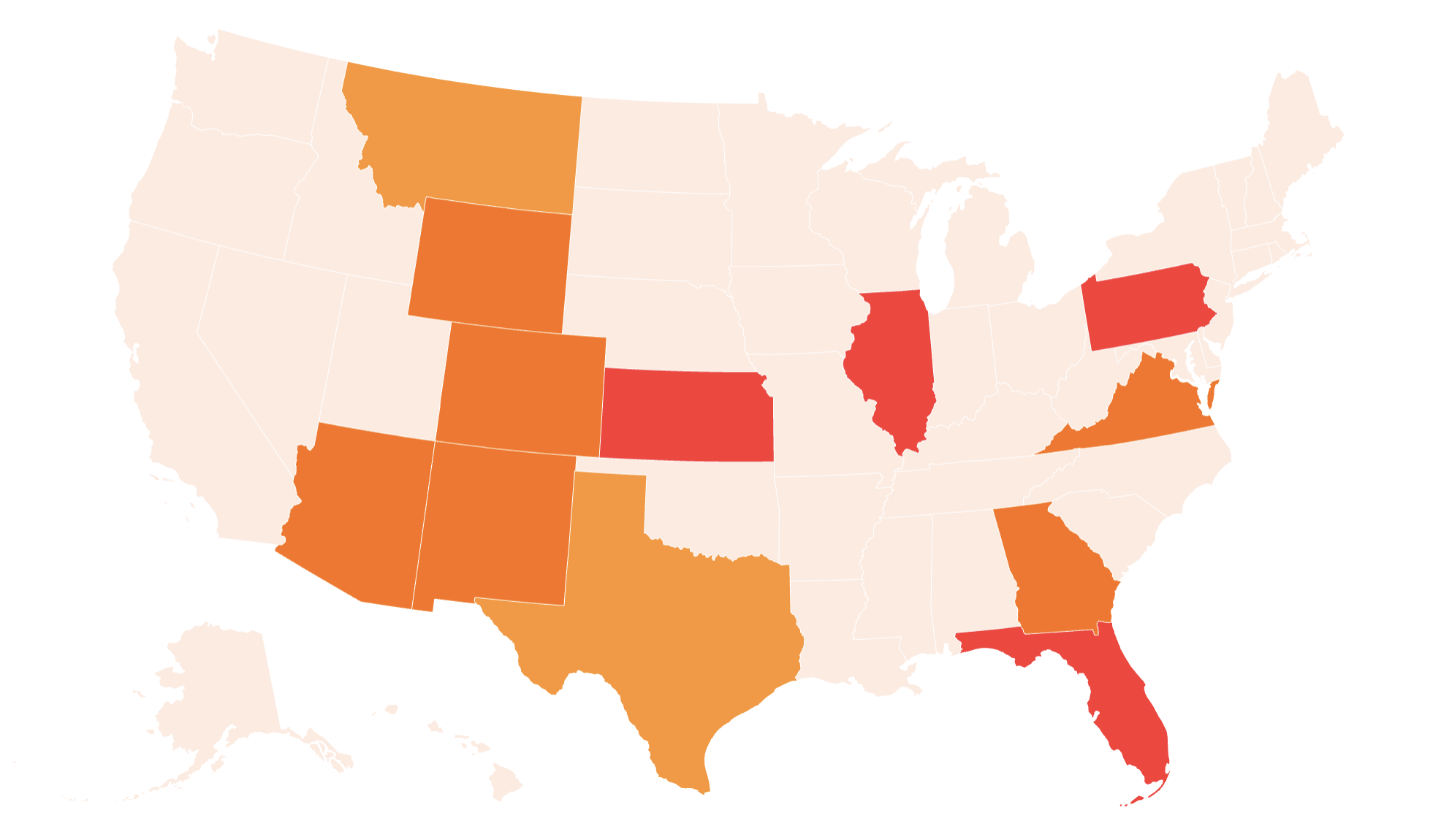

Four states—including Florida, Illinois, Kansas and Pennsylvania—currently have plans to eliminate property taxes entirely. Others—including Texas and Montana—are trying to significantly reduce them.

In Florida, Republican Senator Jonathan Martin introduced Senate Bill 852 after Governor Ron DeSantis expressed on X earlier this year his support for eliminating property taxes entirely.

“I agree that taxing land/property is the more oppressive and ineffective form of taxation,” DeSantis wrote last month.

“Property taxes are local, not state. So we’d need to do a constitutional amendment (requires 60 percent of voters to approve) to eliminate them (which I would support) or even to reform/lower them,” he said. “We should put the boldest amendment on the ballot that has a chance of getting that 60 percent.”

Property taxes are local, not state. So we’d need to do a constitutional amendment (requires 60% of voters to approve) to eliminate them (which I would support) or even to reform/lower them…

We should put the boldest amendment on the ballot that has a chance of getting that… https://t.co/WpOQmjNl0X

— Ron DeSantis (@GovRonDeSantis) February 13, 2025

If passed, the bill would not abolish property taxes but would direct the Sunshine State’s Office of Economic and Demographic Research to create a plan for eliminating them which would keep into consideration alternative revenue through state budget cuts and increased sales taxes.

In Illinois, state Senators Neil Anderson and Dave Syverson co-sponsored Senate Bill 1862, which would create a homestead exemption, effectively eliminating property taxes for homeowners who’ve paid their share on their properties continuously for at least 30 years.

In Kansas, Representative Blake Carpenter pushed forward House Concurrent Resolution 5014, which would generate $2 billion every year in extra revenues by eliminating some sales tax exemptions. This money would then be used to cover the state’s education currently paid for by property taxes.

In Pennsylvania, state Representative Russ Diamond introduced House Bill 900, a draft constitutional amendment that he hopes would go to voters on Election Day. If passed, it would abolish property taxes.

“For me, the ‘big deal’ is that I want people to own their homes and not have to rent from the government, all across Pennsylvania,” Diamond told Fox News Digital.

Should any of these states manage to eliminate property taxes, they would be the first in the country to do so—after similar efforts by other Republican-led states have failed.

Last year, a 63 percent majority of voters in North Dakota rejected a ballot measure that would have effectively banned property taxes based on a home’s assessed value.

Why Is The Movement To Eliminate Property Tax Growing?

For David Schleicher, Walter E. Meyer professor of property and urban law at Yale Law School, the growth of the movement to reduce and eliminate property taxes is “largely a response to the run-up in house prices, particularly in the suburbs and exurbs, that followed the pandemic.”

During and after the pandemic, Schleicher said, there was an explosion in housing demand driven by employees embracing remote work or willing to commute further distances, newly formed households, and homeowners wishing to move to bigger properties.

“Basically, people didn’t want roommates and wanted more space,” Schleicher told Newsweek. “This drove housing prices up and office prices down.”

While this sounds great for homeowners, “and it was,” he said, property taxes skyrocketed as a result of climbing home prices.

“Because property taxes are based on property wealth, and because governments have to balance their budgets in the face of declining—or soon to be declining—commercial property wealth, property taxes on homeowners in a variety of jurisdictions went up,” Schleicher said. “Not the rates necessarily, but the amounts.”

Because property taxes are based on the value of a home, not on their owners’ income, property taxes increased as a percentage of income for homeowners in areas where property prices increased.

“Homeowners got angry about this increase in annual taxes, and they are a powerful force in politics,” Schleicher said.

Jay A. Soled, distinguished professor and chair of the Department of Accounting and Information System at Rutgers Business School, thinks that the growth of the movement also has to do with the U.S.’s greying demographics.

“Those on fixed incomes feel the pressure of increasing rates more than when they were income earners,” he told Newsweek. “As America greys, there may be increasing pressure to reduce property taxes.”

Has Trump’s Return To The White House Boosted The Movement?

Schleicher thinks that the growth of the movement to eliminate property taxes in Republican-led states would have happened with or without Donald Trump.

“I think some of the forces that gave rise to Trump’s return—dissatisfaction with the government and frustration with the changes that happened during the pandemic—played a role,” he said.

“But the biggest reason is simply the increase in property values. Which is ironic, because people generally like it when they become more wealthy,” he added. “But people most prefer to eat the cake of their property value increasing and have tax cuts too.”

While it may seem like Trump’s return to office on a low tax mandate would add fuel to the movement to cut or eliminate property taxes, Caroline Bruckner, a tax professor on the faculty of American University Kogod School of Business, told Newsweek that his administration could have the exact opposite effect.

“The reality is that, with the elimination of so many critical federal agency functions and programs, states may very well have to raise taxes to fill gaps in federal programs and funding that have been cut,” she said.

Tax professionals and business executives that Bruckner has talked to “fully expect to see their federal tax bills to be cut with an extension of the Trump tax cuts and for the states to respond by raising taxes to fill funding gaps from federal funding cuts,” she said.

Daniel Shaviro, Wayne Perry professor of taxation at NYU Law, agrees with this theory, but he is not sure that state governments will follow this logic.

“Radical cuts to federal support of the states should logically push in the opposite direction,” he told Newsweek. “But the Trump administration does stand as an example of fiscal recklessness that may be contagious.”

Can We Do Without Property Taxes?

For a tax that goes back thousands of years, there is very little consensus among economists about whether they are an efficient form of taxation, Schleicher said.

“I’m not sure if your readers want all the nitty-gritty academic back and forth, but my two cents are that the property tax is a pretty good tax as part of a broader mix of taxes, but that having it implemented mostly by small local governments is a mistake,” he explained.

Excessive localism leads to huge inequalities between jurisdictions and strips property taxes of their function of providing homeowners with some protections against property value declines, Schleicher said. But even so, he thinks property taxes make sense as part of a mix of revenue sources.

“Having wealth be the sole basis for taxation would be bad, but splitting taxes between present income (income taxes), consumption (sales taxes) and wealth (property taxes) is wise,” he said. “Whether getting rid of [the property tax] would be a good idea depends a lot on what you’d replace it with.”

Replacing local property taxes with state sales taxes—as some states have proposed—would make the tax system much more regressive and would reduce the degree to which local governments are responsible for producing their own revenue, Schleicher explained.

“I think the former is very bad but the latter is good, at least directionally. There are also ways to reform property taxes to make them punish buildings less, which I favor,” he added. “But that doesn’t seem to be on the menu in these reforms.”

At the moment, property taxes are the easiest way for state and local governments to get funding for crucial public services like schools, roads, police, and fire prevention.

“The houses are right there on the properties and can’t hide anywhere,” Shaviro said. “It’s pretty hard for a local government, especially if it’s small, to tax income, and sales taxes can be avoided by shopping over the jurisdictional boundary.”

Eliminating property taxes would force state and local governments to make tough decisions about what programs to cut funding from.

“This would be a double-whammy for states that are also losing funding from federal programs,” Bruckner said. “In other words, with proposed cuts to key federal agencies that provide funding and services. there will be more pressure on states to step up and deliver critical services for education, healthcare and disaster aid,” she added.

While this might not seem like a big issue now, Bruckner said, “hurricane season is right around the corner. A category 4 or 5 storm can devastate a state’s economy and empty a state’s coffers in terms of providing disaster response.”

Newsweek