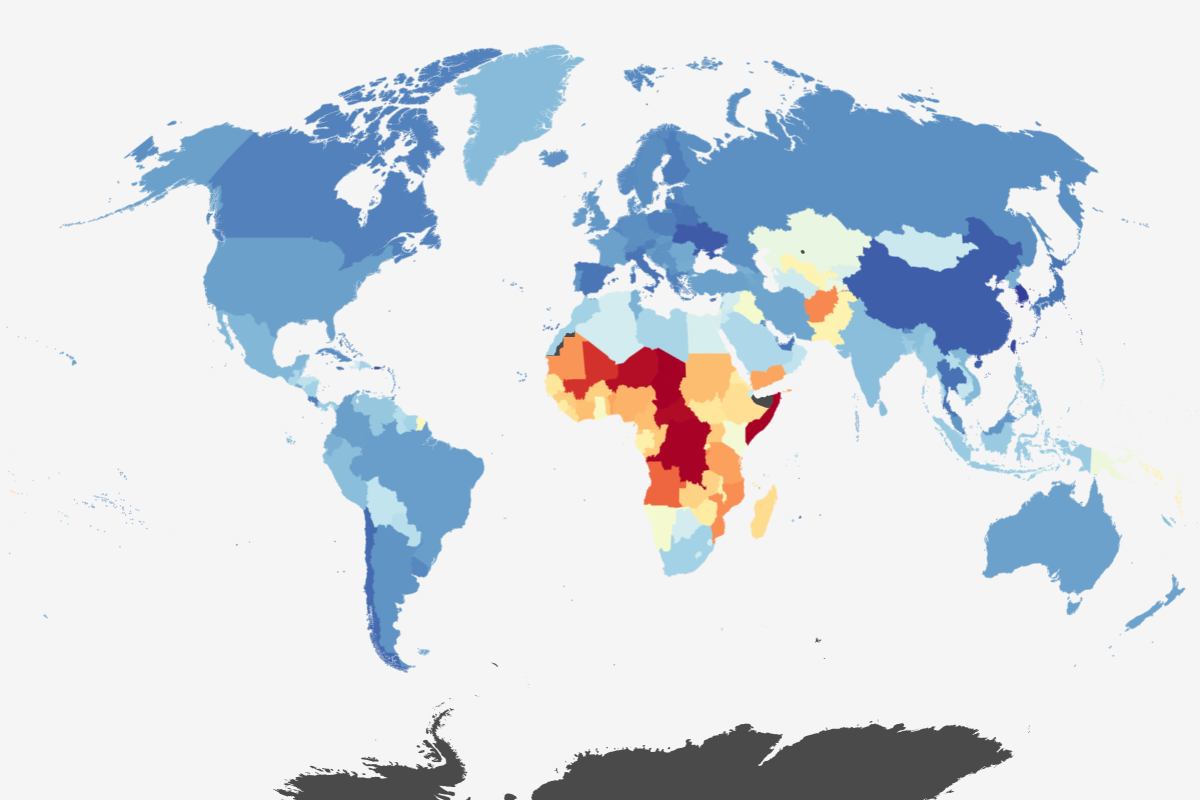

Almost every country in the world has seen fertility rates decline over the past few decades, but one region’s birth rates are still so high that it is expected to provide more than half the global population increase until 2050—sub-Saharan Africa.

The global fertility rate was 2.2 births per woman last year, down from five in the 1960s and 3.3 in 1990, according to the United Nations World Fertility 2024 report. It is set to hit the replacement level of 2.1 (required to maintain a stable population without immigration) in 2050 and drop below the replacement rate to 1.8 in 2100.

America’s fertility rate is already below the replacement rate, at 1.6 births per woman, according to the Congressional Budget Office‘s latest forecast released this year.

But sub-Saharan Africa’s fertility numbers are the highest of any major world region, at 4.3 children per woman. This high figure is despite the fact that the region, made up of 49 separate African nations, has also seen declines—from 6.5 in the 1960s, to 5.3 in 2000.

The UN Commission on Population and Development estimates that over the coming decades, more than half of all new people added to the planet will be in Sub‑Saharan Africa.

“Generally, countries in sub-Saharan Africa are in an earlier stage of the demographic transition, characterized by a relatively large share of children and youth,” Patrick Gerland, chief of the Population Estimates and Projection Section, told Newsweek.

In other words, while countries in the Sahara have followed the rest of the world in lowering death rates, meaning there are more elderly people than there have been before, their higher birth rates mean their populations are mostly children and teenagers.

This means that, unlike wealthy countries, which are facing a workforce crisis (not enough working-aged people to support the growing elderly population), nations in sub-Saharan Africa have a growing working-age population.

But “investments in areas like education and infrastructure will be crucial” for this to be as beneficial as it could be, Gerland said. “Many African countries are currently experiencing a ‘window of opportunity’ for economic growth,” he said.

Could This Be Tomorrow’s Workforce?

Professor Giovanni Peri, an economist at the University of California, spoke this dynamic – a growing workforce in sub-Saharan Africa with “demographic pressures increasing in rich countries as they age, have fewer workers and higher dependency ratios.”

“From an economic point of view, it would make sense to think this would generate change in attitude towards migration,” he told Newsweek. “So far it has not, and it seems unlikely in the next two decades, at least to me.”

“From an economist point of view, any reasonable policy that would plan migration in an orderly way from south-Saharan Africa, to jobs and universities in Europe, enforced and implemented well would generate huge economic gains,” he said. “I just do not see this happening.”

Similarly, William Frey, a demographer and senior fellow at The Brookings Institution, told Newsweek: “It is clear that most developed countries, including the US, will need to rely on immigration to counter advanced population aging and declines in their labor force populations.”

“In the years ahead, the U.S. will require even higher immigration than it currently receives in order to avoid this scenario,” said Frey.

But “the issues of safety, culture will predominate on the economic rationale,” Professor Peri said.

Why Does Sub-Saharan Africa Have Such High Birth Rates?

“Fertility transitions in sub-Saharan Africa exhibit distinctive characteristics compared to other low- and middle-income countries,” the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs said in its report.

“The fertility decline started later, and the pace of fertility decline has been markedly slower in sub-Saharan Africa than in Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean,” it said.

There are many practical reasons for high fertility rates in sub-Saharan Africa, including limited access to contraception, lower levels of education for girls and women and high rates of child marriages.

But there are also significant cultural reasons, with children seen as important contributors to household livelihoods and carers of parents in old age.

Both men and women in sub-Saharan Africa express a preference for larger families—in Burundi, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda and Zimbabwe, the ideal family size is 3.5 and four, according to the latest Demographic and Health Surveys (conducted between 2010 and 2022).

Meanwhile, in Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Niger and Nigeria, the ideal family size is more than six.

Conversely, families in wealthier countries are having fewer children while cultural traditions are shifting away from the prioritization of parenthood in general, according to a new study Newsweek reported on here.