As former chairmen of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)—one appointed by a Democrat, the other by a Republican—we have seen firsthand how the agency operates when it is guided by its mission to uphold the public interest. But in just over two months, President Donald Trump and his handpicked FCC Chair Brendan Carr have upended 90 years of precedent and congressional mandates to transform the agency into a blatantly partisan tool. Instead of acting as an independent regulator, the agency is being weaponized for political retribution under the guise of protecting the First Amendment.

Their actions fall into two categories. First, the president used executive orders (EOs) to strip the agency of its independence, making it subservient to the White House. Second, the chairman has exploited the commission’s powers to undermine the very First Amendment rights it is supposed to uphold.

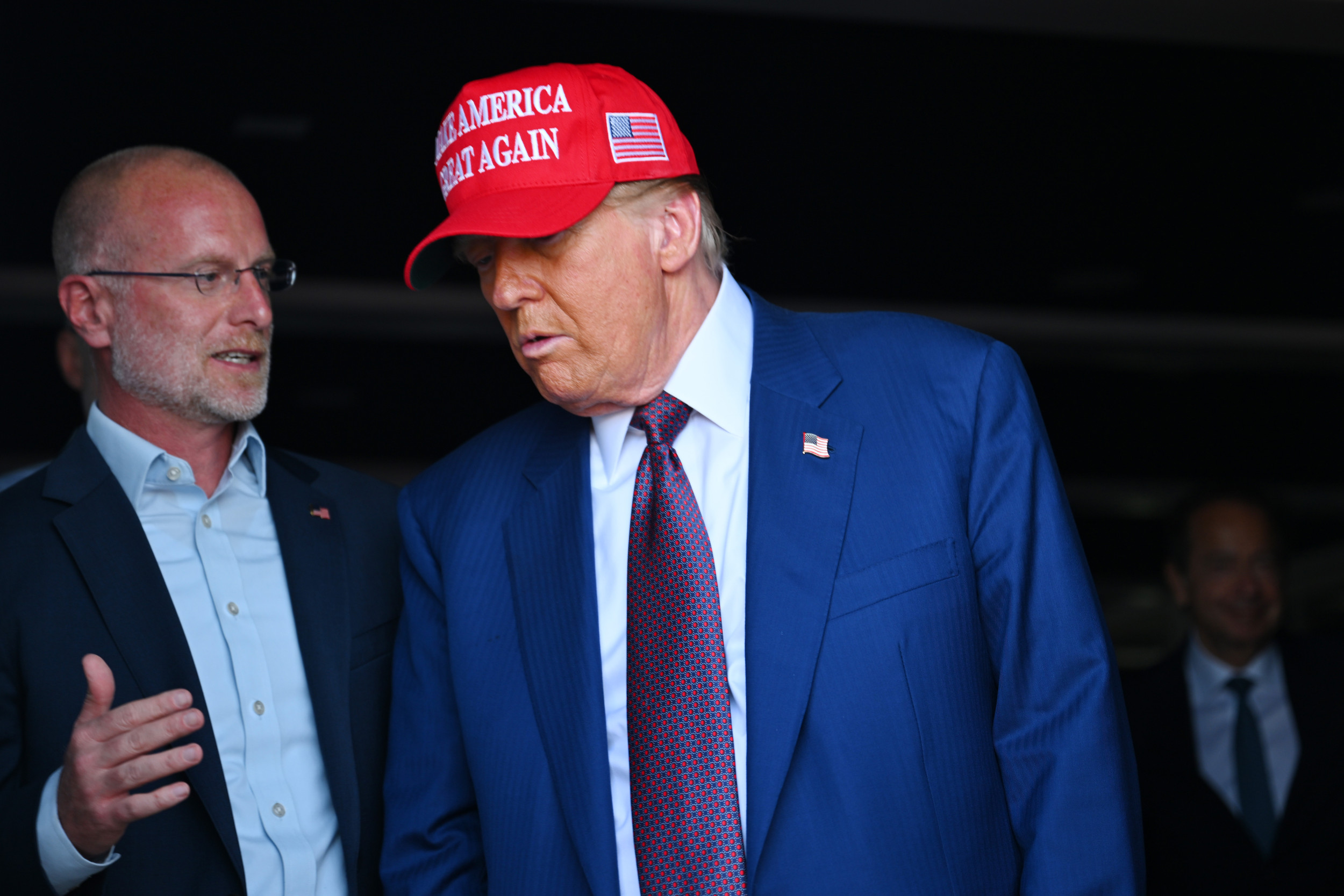

Brandon Bell/Getty Images

Congress established the FCC in 1934 as an independent agency, designed to be “free of the policy aims of the Executive branch” as noted in a 2015 Senate report. But on Feb. 18, President Trump overturned that mandate with an EO requiring all independent agencies to obtain White House approval for “all proposed and final regulatory actions.” The following day, a second EO granted the FCC chairman—and all other Trump-appointed agency heads—unilateral authority to determine whether “ongoing enforcement [actions] in their regulatory review is complaint with the law and Administration policy.” This process bypasses the other Senate-confirmed commissioners and effectively hands the White House control over the FCC’s enforcement decisions.

While the president’s power grab is unprecedented, it is especially egregious that the FCC and its chairman are being used to undermine the First Amendment by claiming to protect the “public interest”—a vague concept whose imprecision invites abuse. Even under its broadest interpretation, however, this standard is subordinate to the First Amendment. The Commission’s own manual states, “The First Amendment, as well as Section 326 of the Communications Act, prohibits the Commission from censoring broadcast material and from interfering with freedom of expression in broadcasting … [and] the public interest is best served by permitting free expression of views.”

Within days of taking office, Chairman Carr weaponized his interpretation of the public interest to reopen a previously closed complaint that echoed candidate Trump’s assertion that CBS‘ editing of an interview with Kamala Harris distorted the facts. As a private citizen, Trump had previously filed a $10 billion lawsuit (later upped to $20 billion) alleging CBS had engaged in “election interference.” By launching its own investigation, the FCC has put its thumb on the scale, transforming the defendant in a private lawsuit into the target of a government investigation and coercing CBS to turn over the unedited transcript of the interview. President Trump piled on, posting on Truth Social that “CBS should lose its license.”

The chairman has also linked the previously dismissed complaint—and by extension, Trump’s lawsuit—to the FCC review of the transfer of CBS‘ broadcast licenses to a new owner as a part of the sale of its parent company, Paramount Global. Not too subtly, Carr warned the lawsuit-related complaint, “Is something that’s likely to arise in the context of the FCC’s review.”

The chairman has also directly challenged editorial decisions by FCC licensees. For example, the FCC has opened an investigation into the decisions of KCBS Radio because its reporting included the location of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids in San Jose, Calif. In an interview on Fox News, Carr questioned whether this reporting was “consistent with their public interest obligations.”

It is not just broadcasters in the Trump FCC’s crosshairs. Despite lacking statutory jurisdiction over online platforms, the FCC has launched an investigation into Big Tech’s editorial practices. In a letter to the CEOs of Alphabet (Google), Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, and Apple, Carr accused them of participating in a “censorship cartel [that is] an affront to Americans’ constitutional freedoms and must be completely dismantled.”

Because these actions are taken unilaterally by the chairman and without a formal commission vote, they bypass judicial review. But the coercive message is clear: companies risk retaliation if they fail to align with the administration’s views. The chilling effect on free speech extends beyond the targeted companies, pressuring others to engage in self-censorship or face the FCC’s wrath.

To his credit, Chairman Carr has proposed initiating a formal rulemaking process before the commission to clarify the meaning of the public interest standard. To his discredit, he has yet to follow through, nor has he publicly outlined the specifics of his definition of what the standard requires. Instead, he has commenced investigations into supposed violations of a standard whose details only he knows.

Using vague government policy as a tool of political coercion is a tactic historically associated with authoritarian regimes. It is now up to Chairman Carr to prevent such abuse by clearly defining his construction of the public interest standard and its relationship to the First Amendment.

Congressional imprecision in passing the Communications Act of 1934 has unfortunately led to a chairman using the agency’s significant powers to intrude into First Amendment-protected free speech. While it’s clear that such intervention is not in the public interest, Congress should explicitly say so.

Tom Wheeler is a former Democratic FCC chair appointed by former President Barack Obama.

Al Sikes is a former Republican FCC chair appointed by former President George H.W. Bush.

The views expressed in this article are the writers’ own.